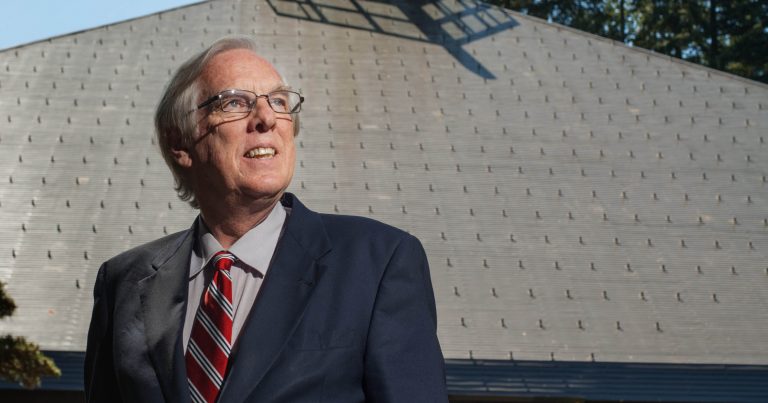

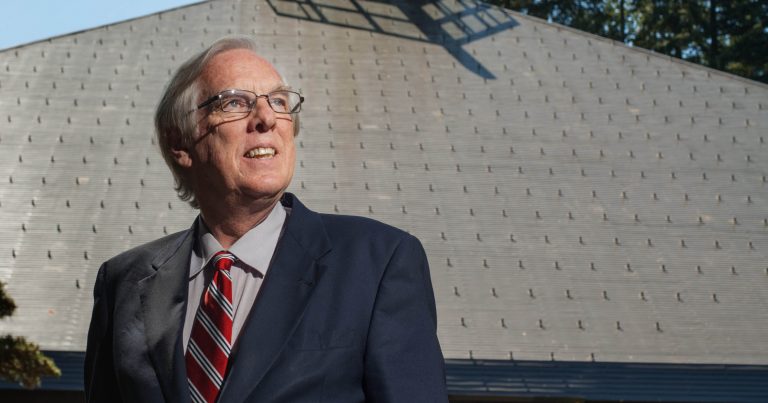

The Asian studies Faculty Spotlight is a new series where we ask our instructors about their early lives, career development and proudest accomplishments. Our first interview features Dr. Donald Baker.

Photo by UBC Marketing/Martin Dee

Quickfacts

- Dr. Don Baker has been teaching at UBC for 29 years!

- Teaching the below 2016W Courses:

ASIA 317 Rise of Korean Civilization (stone age to 1600)

ASIA 337 Korean People in Modern Times ( 1600 to the present day)

ASIA 200 Cultural Foundations of East Asia

ASIA 356 Korean Cinema

- Recent publication: Korean Spirituality (University of Hawaii Press, 2008)

Can you explain to a non-expert what you research?

My research focuses on how Koreans have defined themselves as Koreans over the centuries. Despite having two very large neighbors right next door, Korea has maintained political and cultural independence for most of the last 2,000 years. I want to know how they have managed to do that. I am especially interested in the role religion and philosophy, as well as history-writing, have played in creating and sustaining a distinctive Korean identity.

How and why did you start your journey in Asian Studies?

I got into Asian Studies by accident. I grew up in the deep south in the US and wanted to explore the wider world. As an undergraduate at Louisiana State University, I heard about a government-funded year at the University of Hawaii—if I would agree to study Chinese. I was willing to do anything for a chance to spend a year in Hawaii at no cost to me or my parents, so I applied and was awarded that scholarship, which included not only 12 months in Hawaii but also 3 months in Taiwan. At the end of those 15 months, I was hooked on East Asia. I wanted to return to East Asia after I graduated from LSU, but didn’t have enough money to do so. But then I learned that the US Peace Corps was recruiting volunteers to work in Korea. I thought “how different can Korea be from China?” (How little I knew back then!) I applied to the Peace Corps and ended up teaching English in the southwestern city of Kwangju (now spelled Gwangju) for 3 years. That inspired me to go on to graduate school in Korean history, which I did at the University of Washington. After earning my Ph.D. in Seattle, I moved up the road to Vancouver and UBC (after 4 years of detours to teach at some schools in the US.)

Dr. Baker’s grade 7 class. Can you guess which one he is? Scroll to the bottom of the interview to find out1.

What was the experience for you learning a second language?

I found out that I was offered the scholarship to study Chinese in Hawaii as an experiment to find out if somebody (me) who had a lot of trouble learning European languages (German) could do better at learning an East Asian language. It turned out that I was not better at learning Chinese than I had been at learning German—until I spent a summer in Taiwan. Once I was immersed in the culture using that language, I soaked it right up. The same thing happened later when I lived in Korea with a family that didn’t speak English and, to a lesser extent, when I lived in a small town in Japan with few English speakers. Learning a foreign language from a textbook is, for me, not nearly as efficient as learning that language by being forced to speak it!

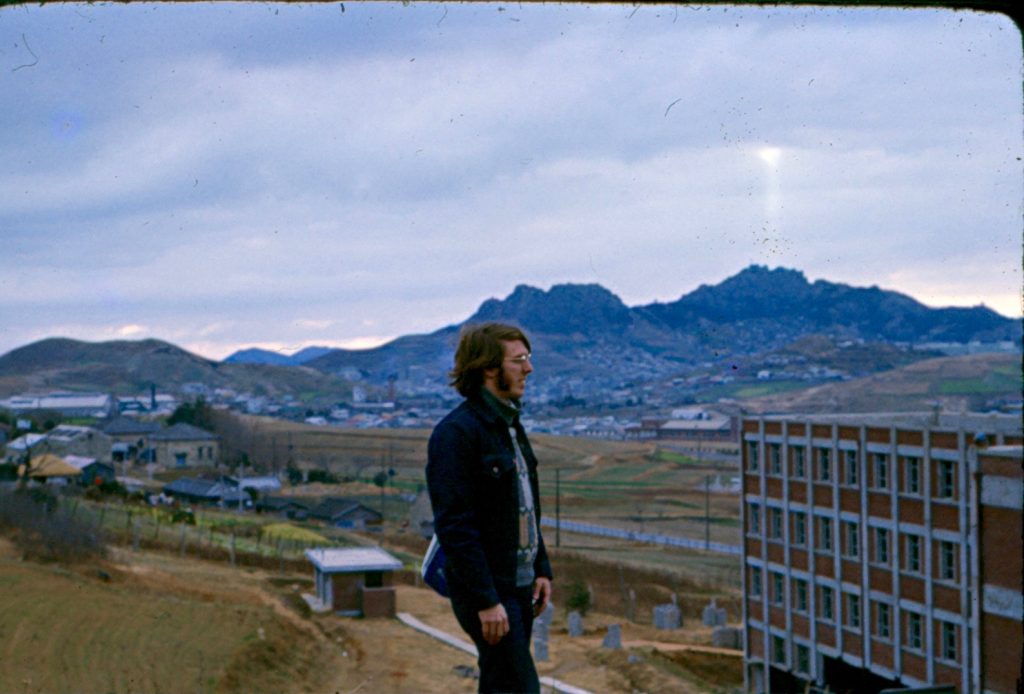

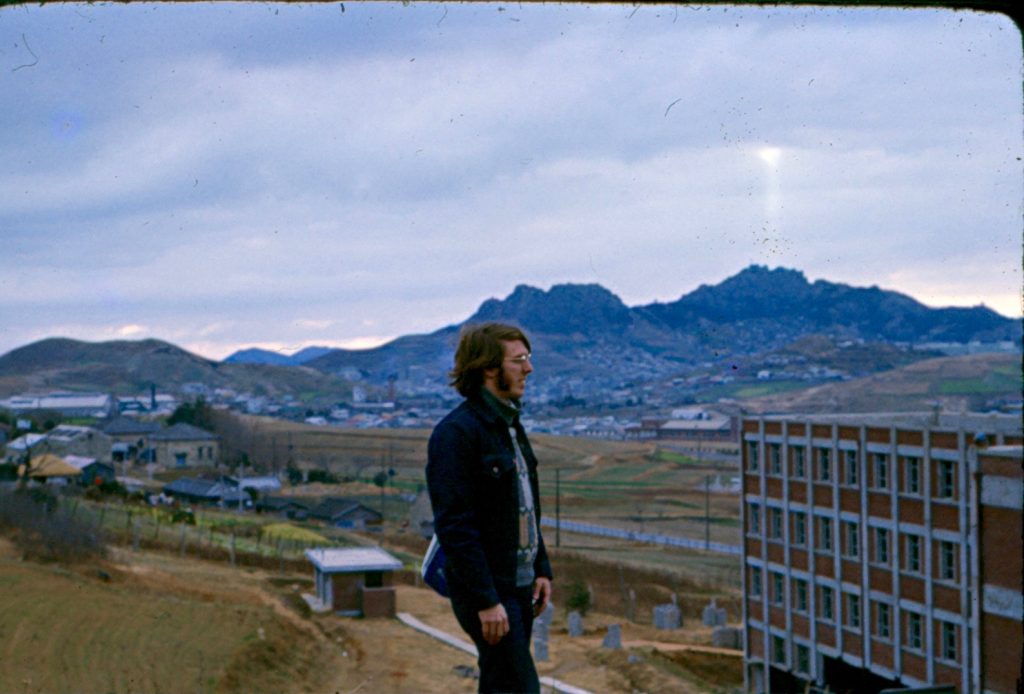

Kwangju 1973. This is a photo of Baker standing on the hill behind the middle school where he taught English.

Was there a point in your journey you struggled or questioned yourself? What happened?

When I finished my Ph.D., there were no jobs in Korean history anywhere in North America. I kept food on the table by filling in at various universities for professors of Chinese or Japanese history on sabbatical leave. I finally landed a full-time, possibly-permanent job at Boise State University in Idaho teaching the histories of Western and East Asian (primarily Chinese and Japanese) civilizations, but that didn’t really give me a chance to use what I had worked so hard to learn in Korea and Seattle. I was about ready to abandon dreams of being a professor of Korean history when UBC called and asked me if I were interested in teaching Korean language and history. I jumped at the chance and haven’t questioned my career choice since.

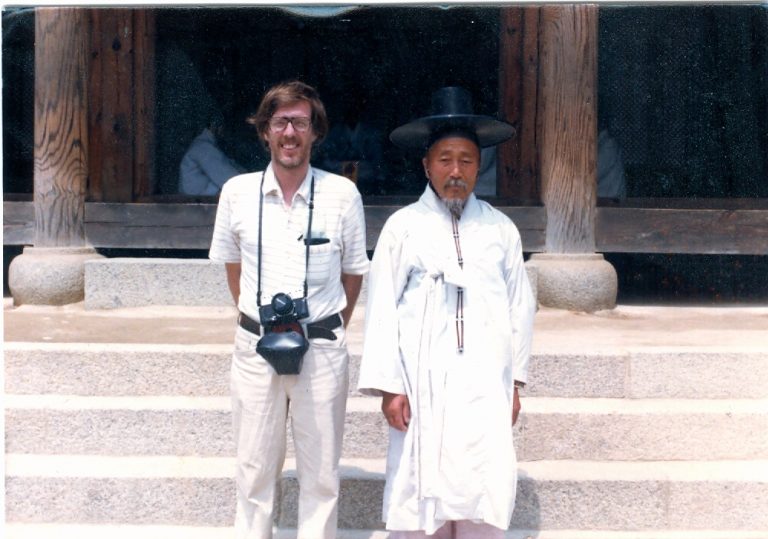

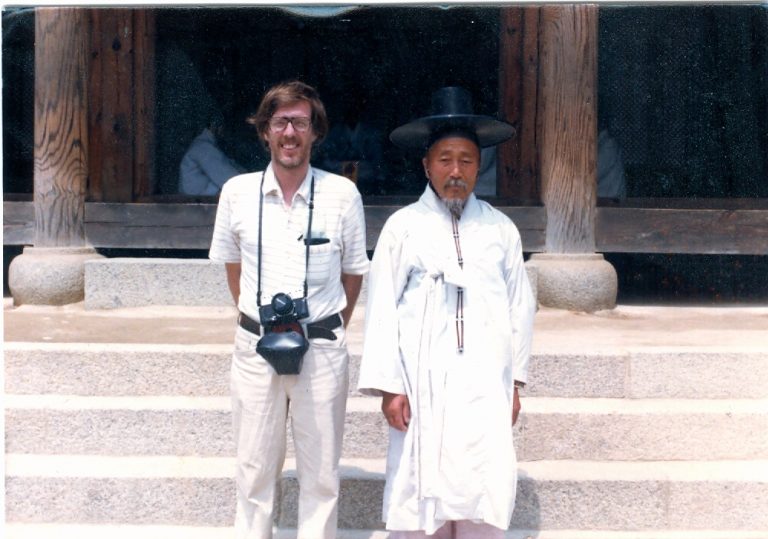

Baker with Confucian Scholar: sometime between 1971 and 1974, in the Korean countryside.

Is there a project that you are most proud of?

I would have to say my work on one of Korea’s greatest, and most original, philosophers, Tasan Chŏng Yagyong (1762-1836), is what I am most proud of. There are very few people outside of Korea who have published research on Tasan’s life and thought, so he still remains pretty much unknown in the Western world. Since I think he has a lot to teach us in the 21st century, I am trying to make him and his ideas better known. I am continuing to publish articles introducing Tasan to scholars who know little about his life and thought, and am also finishing up two books on Tasan, one of which is an English translation of one of his more interesting philosophical works for the way he combines Confucian and Christian ideas.

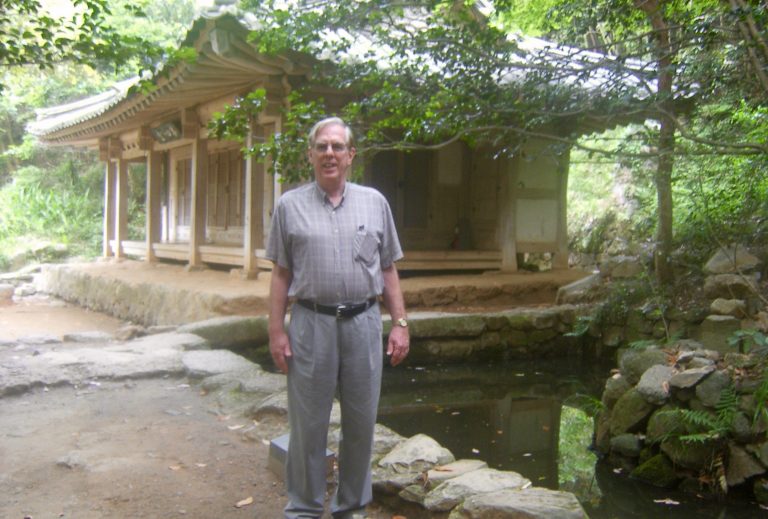

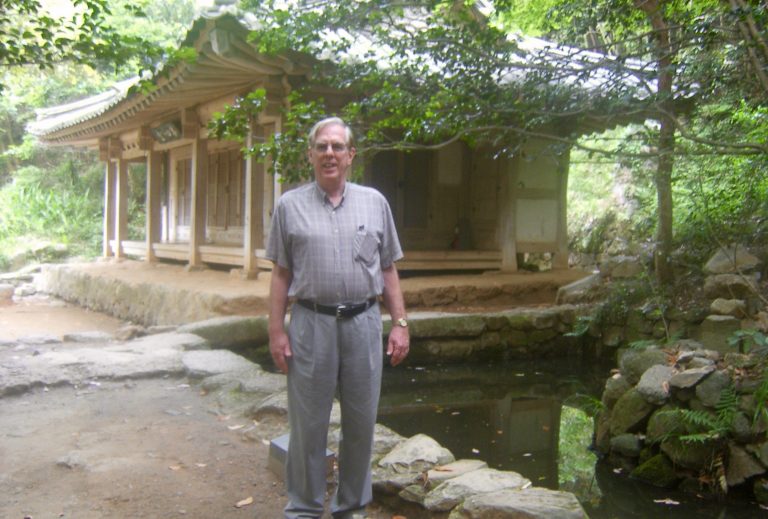

Baker in front of Tasan’s hut. This is the small house Tasan lived in when he had to spend 18 years in exile in the countryside early in the 19th century.

In class we study about events that shape Asia. Have you witnessed any such event firsthand?

Yes, I have, unfortunately. I say “unfortunately,” because I still have very painful memories of what I saw in May 1980 when South Korean special forces troops attacked the unarmed population of what was then South Korea’s 5th largest city, Kwangju. However, as a historian of Korea, I also feel privileged to have been an eye-witness to the most important event in South Korean history since the Korean War. The people of Kwangju were the only people in Korea that spring to rise up in defence of democracy against the military coup launched by General Chun Doo Hwan. Ever since then I have called myself a Kwangjuite, drawing on both my three years there as a Peace Corps volunteer from 1971 to 1971 and as someone who shared the pain of the citizens of Kwangju in May, 1980. I will never forget what I saw there, and I will never stop trying to get my students, both Koreans and non-Koreans alike, to understand that South Koreans enjoy democracy today because hundreds of innocent people shed their blood and lost their lives in Kwangju that spring.

What change do you hope your work can make in the world?

I hope that, first of all, my work will help young Korean-Canadians and even Koreans back in Korea understand how much their parents and grandparents accomplished over the last few decades. When I first went to Korea in 1971, Korea was poor and under military dictatorship. Now South Korea is rich and democratic. That is a remarkable transformation, made possible only because the Korean people themselves worked really hard, and sacrificed a lot, to improve living conditions for themselves and for their children and grandchildren.

I also hope my published work as well as my lectures will help Koreans realize how much they have to be proud of in Korea’s long history. There is much for Koreans to brag about (the world’s first movable metal type, the beautiful Koryŏ celadons, the sophisticated art and philosophy of Chosŏn Korea, etc.) when they look at the accomplishments of their ancestors but sometimes young Koreans don’t seem to realize that. I hope my work can help them feel the pride in their heritage they can rightfully feel.

Also I hope my work will promote a greater understanding around the world of both the distinctiveness of Korean civilizations and the achievements of Koreans over the centuries. Korea is not just Hyundae, Samsung, K-Pop, and TV dramas. There is much more to Korea culture than that. I want to help non-Koreans learn to appreciate, and enjoy, many different aspects of Korean history and culture just as I do.

Baker was asked to participate in a real Confucian ritual in the small city of Andong in Korea in 2014. They paid ritual homage to the great Confucian scholars from past centuries.

1 Dob Baker’s 7th Grade Class. Don Baker is in the 2nd row, at the end on the right (on the opposite side from the nun).