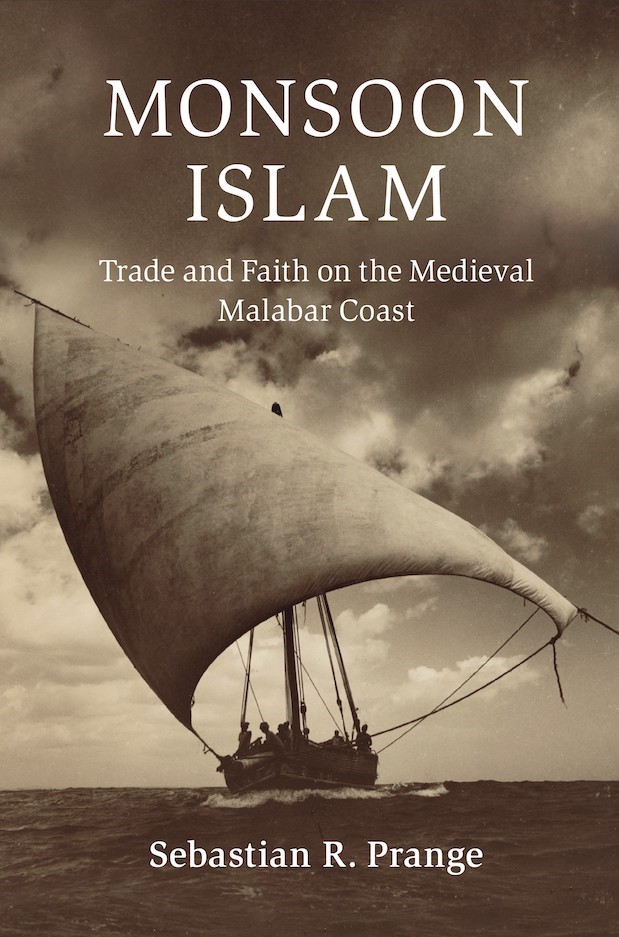

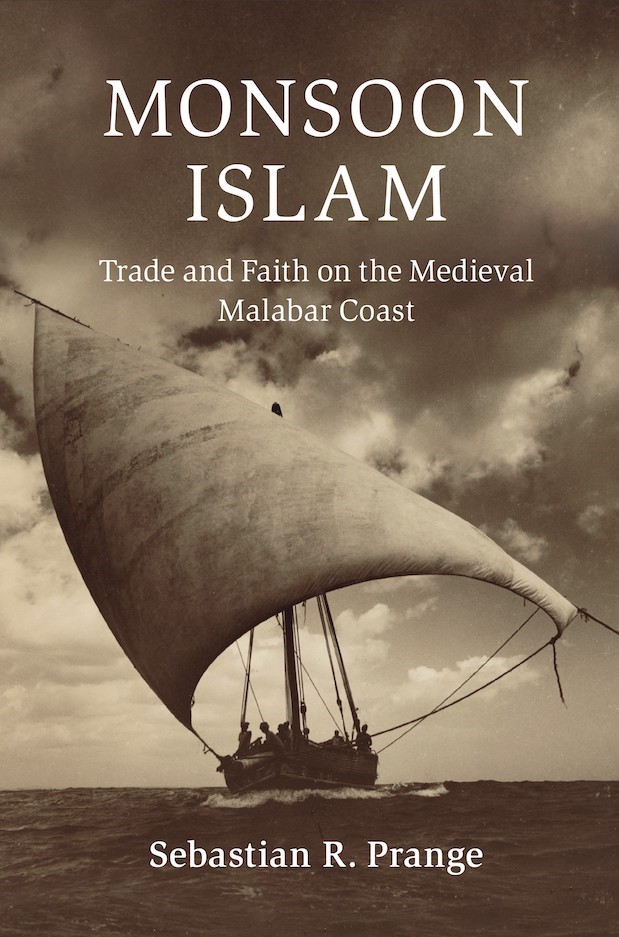

Meet our new faculty members in Asian Studies and learn more about their background and passions! In this Faculty Spotlight, we introduce to you Dr. Sebastian Prange, Associate Professor at the Department of Asian Studies, the University of British Columbia. His research interests revolve around the development of Islam in monsoon Asia, the role of piracy and maritime violence, and the evolution of capitalism from a non-European perspective. Prior to the Department of Asian Studies, Dr. Prange was an Associate Professor at UBC’s Department of History.

Could you tell us a little about your academic background prior to joining UBC Department of Asian Studies? What brought you to Asian Studies?

I had the privilege to study at three different schools within the University of London: Goldsmiths College, the London School of Economics, and the School of Oriental and African Studies. Over the course of these degrees, I became more and more interested in the organization of premodern trade: how did merchants manage to conduct business across immense distances and multiple cultural and linguistic divides? My search for answers to this question led me to specialize in the economic history of medieval India.

After completing my PhD, I found my first job at UBC, as a postdoctoral fellow. Following that, I held positions in Germany and the US before returning to UBC in 2012. Since then, I have taught in the History Department, and am delighted to now transition into the Department of Asian Studies. Having been trained in an area studies institute, and having worked in many different interdisciplinary settings, Asian Studies is a great fit for me – not least for its incredible cohort of South Asia scholars.

Could you explain to a non-expert what you are researching and what inspired you to research this area?

My recent book, Monsoon Islam, examines the development of Islam among merchant communities of the medieval Indian Ocean world. It traces the commercial connections between different regions (East Africa, Arabia, Persia, India, and Southeast Asia) and looks at how merchants served as key vectors in the communication and evolution of Islam in the port cities of South India. I have long been interested in following the routes of commodities to uncover the often convoluted and complex histories of trade and traders – and Kerala’s pepper trade has proven an especially rich case study for this approach.

In my new project, I look at the history of Indian Ocean piracy. The project is premised on the notion that in Asia as in Europe, the early-modern period was marked by a shift from fluid to more rigid parameters of social and political identity, from semi-private to public forms of warfare, and from personal to increasingly codified legal regimes. Recognizing that maritime violence was a crucial dimension in all of these developments recasts the much-maligned pirate as a key player in the making of the early-modern world.

Can you tell us what you will be teaching in UBC Department of Asian Studies?

This year, I will be teaching a course on the History of the Indian World (ASIA 390) that is very close to my heart. We will examine the vital role that maritime connections – as well as competition and conflicts over the sea – have played, not just for the history of Asia but in a world-historical context. By looking at ships and seafaring, mobility and culture, trade and economics, as well as politics and imperialism, we will open up multiple alternative vantage points on this history that a more conventional, land-based perspective tends to obscure.

In the coming years, I look forward to developing new Asian Studies courses on the economic history of Indian and on the relationship between trade and religion in Asian history.

What do you want students to gain out of your courses?

Aside from the specific content and skills we work on in my different courses, their collective aim is to look at history from new perspectives. This includes bringing in the voices and experiences of different actors (say, those of ordinary merchants rather than political elites), but also to instill ourselves into worlds that, at first glance, seem very remote and different to our own. Studying premodern history challenges us to engage with completely unfamiliar assumptions, values, constraints, and identities – an intellectual endeavour that can be both unsettling and revelatory.

Can you tell us something positive (whether related to your academic career or not) that 2020 produced for you?

Clearly, the costs and consequences of this annus horribilis have been very unequally distributed, both internationally as well as within individual societies. It is very difficult to answer this question in view of the incomprehensible loss and trauma that the pandemic has wrought and continues to create.

Something worthwhile to reflect on, and perhaps look for ways to maintain, is how online teaching has collapsed some of the traditional divides between teacher and learner. Working together to find new ways to communicate and share ideas, to engage with course materials, and to create intellectual communities has produced a very different sense of a what a classroom is and can be. I hope we can avoid a simple return to “business as usual” and instead build on some of the new approaches we have experimented with together over the past year.