Interested in pursuing an MA or PhD in Asian Studies? In this interview series, we ask our graduate students about their research, their experience in our program and their future academic and professional goals. This interview features PhD student Casey Collins. Casey’s research focuses on Modern Japanese & Korean Religion.

Tell us a little about yourself, your background and how you became interested in Asian Studies?

I’m originally from the San Francisco Bay Area and first moved to Vancouver in 2005 when I started my BA at UBC. I found out about Asian Studies by following an interest in South Asian music, history, languages, and religions.

Why did you choose the Asian Studies program at UBC? Was there an aspect of the program or location that was particularly attractive to you compared to other programs in Canada or internationally?

When I was 16, my grandparents gave me an opportunity to come to a summer camp at UBC. We drove up together from California and they dropped me off at Totem Park to stay with other high school kids from all over the world for a few days. I remember reading Harry Potter in the car and feeling like I was going to Hogwarts. During that short stay I fell in love with the UBC campus and learned about the variety of courses available in Asian Studies. I started considering Asian Studies as a potential major when I took ‘Intro to Asian Studies’ with Dr. Harlow.

Asian Studies is an unusual field. Not every university has it or calls it the same thing, and within the department at UBC a number of academic disciplines are represented. I had a number of interests as an undergraduate student, and the Asian Studies BA program allowed me to explore many of them. Asian Studies gave me a change to study religion, history, art, language, literature, and a bunch of other topics, including a whole year of astronomy. It was exactly what I wanted most out of those four years.

Could you explain to a non-expert what you are researching and why it is important?

I study contemporary Japanese and Korean esoteric Buddhism and new religious movements. Religion, much like language, ethnicity, gender, and status, is also tied to modern identities and is a dynamic and vital force all around the world. Societies navigate the relationship between religion and public life in a variety of ways. We may form secular democracies, or have a state religion, for example. Many nations even reserve the right to determine which religions are “real” or “good,” and which are not. Studying this relationship yields insights into power, oppression, and the history of ideas that shape how we think about ourselves and others.

Studying religion is less about learning the names of deities or reading scriptures, and more about analyzing humanity’s many ideas about the world and how we are to live in it. As such, the field of religious studies is germane to a number of current affairs, and religion in contemporary society intersects with matters such as public policy, globalization, and even violence. A close look at nearly any page in a newspaper will almost certainly reveal some connection to religion or a discourse about religion. It is not difficult to see that this topic grabs our attention and is a part of public life, even in a secular society where we might just as soon ignore it. This in itself seems to me a very good reason to seek a greater understanding of religion.

I mainly study Japanese and Korean religions that emerged within the last one-hundred years or so, including modern Buddhist institutions. We might not often hear about most of these religions in Vancouver, although many do have a small presence here. Some of them play an important role in East Asian public life, even though many are marginalized or popularly regarded as bizarre. Sometimes these religions become mainstream traditions, and sometimes they are polemically referred to as “cults” or even terrorist organizations.

Members often retain their “modern” identities as partners, parents, or professionals, while also being part of their religious community, perhaps even taking on leadership roles not accorded to them in mainstream society. These movements are “different worlds to live in,” to quote George Santayana. They permeate and overlap with secular society in East Asia and around the world, even as they offer alternate identities, different ways to live in modernity, and membership in transnational organizations.

Within a few months of graduating from UBC I moved to Japan to work for a Buddhist-derived new religious movement called Shinnyo-en, which was founded in the 1930s, became independent from the Shingon denomination in the 1950s, and has since grown into a wealthy transnational lay-oriented Buddhist organization. I lived in Tokyo for three years while working at Shinnyo-en’s head temple. It was a valuable and challenging experience, one that forced me to seriously consider how people live as members of a new and marginalized religious tradition. While there, I saw how beliefs and practices inherited from the thousand year-old Shingon tradition are given completely new meanings, and I began asking questions about contemporary religious institutions, hierarchy, gender, race, and the discourse of religious legitimacy.

As I became more fascinated by these questions, I decided to consider postgraduate studies. So I contacted my mentors at UBC, travelled and studied as much as I could in Japan, and then quit my job. I did not think of postgraduate studies as a way to “find myself,” but it has offered me the opportunity to consider difficult questions, test my ideas, and strive for new knowledge.

As a graduate student, what are your main activities?

For the last two years, I’ve been mainly reading, studying Korean, and taking courses. I just began comprehensive exams and am also getting some practice with teaching. I have also had the pleasure of working with my supervisor, Dr. Jessica Main, The Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation Chair in Buddhism and Contemporary Society, to host visiting Buddhist studies scholars for speaking events and an annual conference at UBC.

What has been the most memorable or impactful moment of your graduate experience?

So far, I think it was writing my MA thesis a couple years ago. It took months of focused study, composition, and rethinking on my part, but as a process it really involved the input of many people, including my professors, my family, and my friends. It made an impact on me because I saw that research and writing have a collaborative component that is essential and rewarding. My supervisors, Jessica Main and Edward Slingerland, and other professors were very generous and supportive in helping me navigate existing scholarship, experiment with different ideas, and then think through things on my own. My mom spent hours listening to me talk through ideas on the phone. The experience showed me how my own contributions to my field are built upon those of other people, and will in turn be built upon by others. The whole process was challenging, but it also helped me relax, gain some perspective on my studies, and feel connected to the scholarly community.

What are your goals (career or academic) once you’ve completed the program? And how is our program helping you achieve them?

Although I try not to worry too much about this question quite yet, I do hope to get an academic job. I find religion and contemporary society endlessly fascinating, and I want to explore that passion through research and teaching.

Asian Studies has given me many opportunities to prepare for a job in the academic community through work opportunities, participation in conferences, and professional development courses. Just last year, the department very generously helped interested graduate students attend the Association of Asian Studies conference in Seattle. On the whole, the Asian Studies Department at UBC has been tremendously supportive in helping us prepare for the future and meet our goals. I am most grateful for the professors’ generosity with their time, ideas, and support.

Can you give any advice to new students in our program or for students considering applying to it?

If at all possible, travel! No matter what you are doing during that time or how challenging it may be, none of that time will be wasted, and the personal and intellectual fruits of your adventures will continue to emerge throughout your time at UBC and beyond.

And read novels. Stories help open and refresh our minds, especially those that are completely unrelated to whatever you are studying. I find that books help me to reconsider “big picture” ideas and keep me somewhat sane. For some people live music, a trip to an art gallery, or a hike in the North Shore Mountains will do the same thing. Whatever it is for you, find it and feed it and flourish in your studies.

Recent News

Featured Courses, Students

Asian Studies courses to take in Winter 2025 Term 1

July 8, 2025

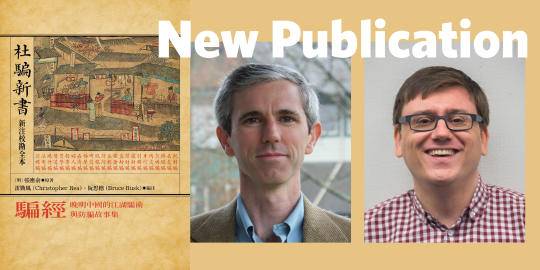

Alumni, Announcements, Faculty, Graduate, Publications

Drs. Christopher Rea and Bruce Rusk edit China’s earliest collection of swindle stories

June 30, 2025

Featured Courses, Students

New 2025 courses offered in the Department of Asian Studies

June 4, 2025